Football, often described as the world’s game, unites billions across borders, cultures, and political systems. Yet, its global and continental governing bodies—FIFA and the Confederation of African Football (CAF)—are increasingly mired in governance practices that undermine the democratic principles cherished by many nations.

The unopposed candidacies of FIFA President Gianni Infantino and CAF President Patrice Motsepe in their respective re-election bids expose a fundamental flaw in football’s leadership structure. This lack of competitive elections stands in stark contrast to the democratic ideals upheld by heads of state worldwide, who subject themselves to popular mandates and contested elections. Governments, except for autocratic regimes like those in certain Arab states or despotic systems such as Russia’s, should reconsider funding football activities until these organizations align their governance with principles of accountability and transparency.

The Problem with Unopposed Candidacies

Gianni Infantino has led FIFA since 2016, navigating the organization through the aftermath of corruption scandals while consolidating his power. In 2023, he secured another term as FIFA president without opposition, a scenario that raises questions about the democratic integrity of the organization. Similarly, Patrice Motsepe, CAF’s president since 2021, faced no challengers in his re-election bid, cementing his leadership in African football. While both leaders may point to achievements – Infantino’s expansion of the World Cup and Motsepe’s efforts to stabilize CAF’s finances – the absence of contested elections undermines their legitimacy.

Unopposed candidacies suggest either overwhelming consensus or, more troublingly, systemic barriers to competition. In FIFA and CAF, the latter appears more likely. Complex nomination processes, high financial and logistical barriers, and allegations of political maneuvering deter potential candidates. This creates a culture of entrenchment, where incumbents face little scrutiny and alternative voices are silenced. Such practices are antithetical to the democratic principles that heads of state in most countries uphold through regular, contested elections.

A Contrast with Democratic Governance

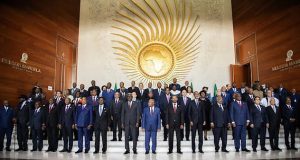

Heads of state in democratic nations – whether in Europe, Africa, Asia, or the Americas – subject themselves to the will of the people. From South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa to Germany’s Chancellor, leaders campaign, debate, and face opposition to earn their mandates. Even in less perfect democracies, the principle of choice remains sacrosanct. Yet, FIFA and CAF operate as quasi-monarchies, where leaders are effectively anointed rather than elected. This disconnect is particularly glaring when governments, accountable to taxpayers, fund football activities overseen by these bodies.

Football is not merely a sport; it is a cultural and economic force. Governments invest billions in stadiums, youth programs, and national team activities, often justifying these expenditures as public goods. In 2022, for instance, South Africa’s government allocated millions to support football development, while countries like Brazil and Germany regularly fund infrastructure tied to FIFA events. These investments are channeled through organizations whose leaders evade the democratic scrutiny that elected officials endure. This misalignment is unsustainable and erodes public trust.

Why Governments Should Act

Democratic governments have a moral and practical obligation to demand accountability from institutions they support. FIFA and CAF rely on public funds, whether directly through government grants or indirectly through hosting tournaments and developing football infrastructure. By continuing to finance these organizations without addressing their governance flaws, governments implicitly endorse undemocratic practices. This is particularly problematic for nations that champion electoral integrity on the global stage.

The exceptions—autocratic regimes like those in certain Arab states or Russia—may tolerate unopposed leadership in football, as it mirrors their own political systems. For instance, Qatar’s hosting of the 2022 World Cup and Russia’s 2018 tournament aligned with their centralized governance models. But democratic nations, from Nigeria to Norway, should hold FIFA and CAF to a higher standard. Withholding funding until these bodies implement competitive elections would send a powerful message: organizations that benefit from public resources must reflect public values.

The Path Forward

Governments can take concrete steps to address this issue. First, they should collectively demand reforms in FIFA and CAF’s electoral processes, including transparent nomination criteria and reduced barriers for candidates. Second, they can condition funding on governance improvements, tying grants or tournament hosting rights to measurable progress in democratization. Third, national football associations, often influenced by government support, should be encouraged to nominate alternative candidates and foster debate within these bodies.

Critics may argue that defunding football risks harming grassroots development or national teams. However, targeted measures—such as redirecting funds to local clubs or independent youth programs—can mitigate this. The goal is not to dismantle football but to ensure its governance reflects the democratic ethos of the nations that sustain it.

Conclusion

The unopposed candidacies of Gianni Infantino and Patrice Motsepe are not mere administrative quirks; they are symptoms of a deeper malaise in football governance. As heads of state submit to the rigors of popular elections, they should not tolerate unaccountable leadership in organizations that rely on public support. Democratic governments, except those beholden to autocratic or despotic systems, must reconsider funding football activities until FIFA and CAF embrace competitive elections. Only then can the world’s game truly reflect the values of the people it claims to represent.